Senator Nikil Saval has been representing Pennsylvania’s first congressional district in the center of Philadelphia since he was elected in 2022. Growing up in West Los Angeles, Saval is the son of two Indian immigrants, both of whom moved to the United States from Bangalore.

As a child, Saval spent his days in his parents’ pizza parlor around workers from all walks of life. According to the PA State Senate website, “His family’s experiences, as immigrants and as small business owners, were formative for Saval, giving shape to his perspective on workers’ rights and his first experiences with solidarity.”

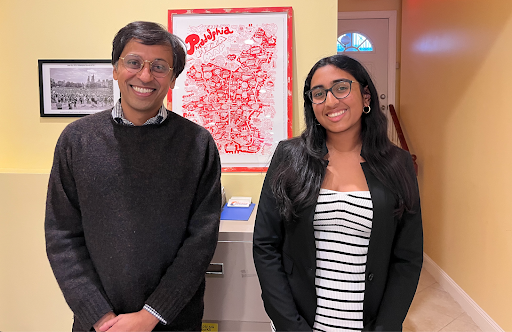

I had the unique opportunity to sit down with the Senator and have a conversation. The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

First, tell me your story

Since I was a child, my main ambition in life was to be a writer. I loved novels, I loved literature. Those were the things I cared the most about. In some ways those are the things I still care the most about. Art and literature are the things we live for and are the things that tell us about our lives and why we live.

I was a journalist and I did a PhD in English literature. But a few things put me on the path of becoming more involved in politics.

The first was the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq when I was in college. I became deeply opposed to those wars. I was horrified by the way that the United States launched these illegal and catastrophic invasions, the harms of which will be felt for generations. That experience led me into deeply questioning the basis of the political order that I was in.

I was trying to understand that, despite the great revulsion and opposition from a lot of people within the United States [to these wars, the] majority of the people that were opposed to the wars weren’t sufficiently powerful or organized enough to stop them. So, I was like “what are forms of political organization that lead us to political power such that we can build a world that is more just and humane so we don’t do things like this? That led me to getting involved in the labor movement.

When I was in graduate school at Stanford to study English, I got involved with a labor union called Unite Here, which is a labor union of hospitality workers. They represent hotel workers, food services, airports, stadiums, arenas. It was the first time I was involved in an organization that was multiracial, working class, and that had political power in a very expensive city like San Francisco and in the region. I was deeply transformed by that experience.

The fight took me into not just working with hotels and stadiums but also representing workers in the school district of Philadelphia. Seeing the way that worker power was related to and led to political power, was something that first transformed my political consciousness into action.

The second thing would be the Bernie Sanders campaign in 2016. I was transfixed by the experience. I was canvassing my own neighborhood and found people who were open to a message of deep political transformation, the kind that I had been seeking, ever since the political response to the war on terror. After Bernie lost, even though he did much better than anyone expected, I formed a political organization called Reclaim Philadelphia, which is a local progressive organization that was meant to instantiate and make real locally the political transformation that people were demanding nationally with the Sanders campaign.

I became elected as a local neighborhood Democratic ward leader through all of this momentum organizing. We were like, “there’s just so much energy to do something,” we wanted to keep channeling it in the right direction. After achieving a measure of political power through this work, someone recruited me to run for state senate. Basically, they were like, “we were looking as an organization and as people, to find someone to run,” and someone just, basically turned me over, saying “why don’t you run?”

You mentioned your previous job experience as a labor organizer. How do you think that informs your work that you do and how does that impact you, both positively and negatively?

I fundamentally see the labor movement as the foundational building block for any kind of world of justice that we seek to build. Doing that work as a labor organizer, I was always a volunteer, to be clear.

I ran big anti-corporate campaigns against hotels and big institutions, [and] I became ready to confront big wealthy interests. I think the way that politicians who don’t come from social movements work is they’ll lend support, or they’ll sign letters, but I think we’re constantly trying to find ways to campaign alongside labor organizers and have our office be an open door for organizing. We really want to be in deep relation to the labor movement and other social movements.

It’s obvious you value being on the ground, You were also just recently named one of the most influential people in Philadelphia magazine, and they call you a man of the people. How have you grown into that over the years? How have you learned to be fully comfortable with that title?

I wouldn’t say I’m comfortable with any of the titles. I would say that the way I try to approach this job is not to feel fully comfortable with the way that American politics is centered around particular people with political charisma or special powers.

Those are just tools of politics. I’m not inherently better than anyone for this job. There’s nothing natural in me that makes me a good state senator or political figure. It’s through organization [and] collective power that we will have any power, that comes through my training as an organizer. That’s how I try to keep myself level with the constituents we serve and the people we work with.

You mentioned not being fully comfortable with your name in the limelight. It must be a change for you to go from just organizing in the Bay Area to now, being a state senator across the country. That means you get media attention. How do you handle that?

I would say that it’s helpful to think about what it’s for, right? What do you do? What are media mentions for? I was a writer, right? I’ve had bylines but I’ve always enjoyed editing. I was a literary magazine editor, [and] there was way more pleasure in editing pieces and seeing the results, because you were still working [on] something that you really were proud of, that got published, that your name wasn’t on.

I feel like I take the same attitude towards working with publicity, or, attention, like you want the attention to drive results fundamentally. It’s for building more political power for the people, movements, and communities that we’re hoping to impact through this job.

Could you talk about your Whole Homes Repair program? What was it like formulating that? Who did you work with to bring that dream of yours to fruition? What was the process like?

Whole Home Repairs is a statewide program in Pennsylvania that is meant to be a one-stop shop for home repairs and for other federal programs that are meant to help make it easier for people to stay in their homes.

[This] also helps provide job training and support for people to get trained in construction trades, the home repair industry, [and] energy efficiency. We knew that there were a huge number of low-income homeowners and tenants in buildings that belonged to small landlords who were at risk of losing their homes.

Because of deferred maintenance issues, or physical disability, the home wasn’t suited to their changing physical needs. Part of [solving the affordable housing crisis] is preserving these homes so that they don’t fall into disrepair, get demolished, [or] sold off.

The real question was whether a solution to this issue could be applied across the state. We started to look at federal programs. There’s a program called Weatherization Assistance, which is meant to help you lower your utility bills by making your home more resilient. A lot of people don’t get access to it because they have deferred maintenance issues.

In Pennsylvania, there were about 10,000 people who were eligible for weatherization but couldn’t get access to the program. We knew that it was a statewide issue already, and that meant there could be a statewide solution: fund home repairs [and] unlock all the federal dollars that are available to you. There were three pillars that immediately emerged: the repairs, the braiding of federal, state, and local programs, and the job training. That’s how we developed the policy for law and repairs.

As we were developing legislation, we brought in a statewide organization called Pennsylvania Stands Up. There was a statewide organization that mainly worked with immigrants called Make the Road. A number of different organizations and institutions were involved in crafting legislation from the get-go. That led to an enormous amount of media attention on the issue of deferred maintenance.

There was a TV spot in Lancaster about how this program could benefit people. That TV spot reached all of Central Pennsylvania. It meant that Republicans and Democrats were drawn to this idea. We had hearings, first through the Democratic Policy Committee and then bipartisan hearings, to draw attention to this issue in rural and urban areas. We got polling for whole home repairs to show how many people would benefit from it. We built a huge amount of support for it.

Finally, there was a lot of federal money available from the American Rescue Plan. We pushed to get money through the budget to get this program adopted. Fundamentally, because we had bipartisan support and federal money, it worked. The program was adopted in July of 2022. That’s how we were able to win it.

I was recently reading that you were part of a push to get Diwali signed as an official holiday in the Commonwealth. Was the process similar to getting Whole Home Repairs approved? And I know Josh Shapiro ended up signing up on that. What was that experience like?

It was something I wanted to do since coming into office. Diwali is one of these holidays associated with the South Asian diaspora and the subcontinent. It’s a major holiday for so many people across the world, including here in Pennsylvania and the United States.

I was the first South Asian elected to the state legislature, so it was hard when you’re by yourself. You need a partner to advance issues relevant to our communities. Amazingly, that partner was a Republican in central Pennsylvania, Greg Rothman, who approached me about it because he has a large South Asian community in his district.

We talked about this idea of doing a bipartisan bill to recognize Diwali. Then there was a House companion bill led by Arvind Venkat, who is the first Indian American in the state House. Ultimately, it wasn’t as much of a big campaign effort because there was no money involved. But, it did involve a lot of effort, as there are big and small South Asian communities everywhere in the Commonwealth.

Ultimately, I think it was about recognizing our communities in this way and acknowledging traditions important to the South Asian community. There’s still more to do. Diwali is significant, but there are related initiatives, like advancing Asian American studies in our public school curricula. At a national level, Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal has advanced legislation about heart health, specifically addressing how South Asians tend to be disproportionately affected by heart disease.

You said, politics is rigorous and relentless. How do you balance family life? Are there certain boundaries that you set, certain things that you do to make sure that work stays at work?

Yeah, it is hard. I would say that it’s better than I thought it was gonna be. I have an office that really respects [and] supports me, and we support each other, trying not to work all the time and ensure that people do have time because my colleagues have children. But also, even if you don’t have children, you have projects and lives, right?

I usually take my children to their piano lesson or whatever sports thing they have to do. I take my kids to school pretty much every morning, and I’m usually home for dinner. The hardest thing is to be home in the evenings.

There are inevitably events, and sometimes you just have to say no to things. Again, it’s not because you’re not dedicated. You have to serve your constituents and ensure you’re doing your utmost to do that, but spreading yourself too thin means you’re much less effective, I think, as a public servant.