Mason Fullerton '25

On March 21, 2023, Tiktok’s Newsroom released the headline: “Celebrating Our Thriving Community of 150 Million Americans!” They weren’t exaggerating. According to studies done by the Pew Research Center, the app can be found on 63% of American teenagers’ phones and one-third of American adults’ phones. Exactly one year after Tiktok’s celebratory headline, U.S. lawmakers decided it was time to change these statistics.

Although 2024’s ‘Ban-Or-Sell’ bill was the first to threaten everyday Americans’ access to TikTok, the suspicions that fuel it have been influencing government policies for over five years.

In 2019, the Federal Committee on Foreign Investment launched an official investigation of the app and its history. The fact that TikTok was created by a Chinese company, combined with reports from the Washington Post that TikTok moderators were instructed to censor content relating to Chinese political issues, such as the Tiananmen Square massacre and Tibetan independence, fed the suspicion that the political interests of the Chinese government were steering TikTok.

In December of 2022, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Chris Wray announced that the Chinese government’s alleged influence over TikTok’s algorithm “allows them to manipulate content, and if they want to, to use it for influence operations.”

At a presentation at the University of Michigan, Wray elaborated, “All of these things are in the hands of a government that doesn’t share our values, and that has a mission that’s very much at odds with what’s in the best interests of the United States. That should concern us.”

This notion is the crux of the American government’s motivation to ban TikTok.

“Congress is fine with the expression,” Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Roberts stated in response to the ban’s potential to trigger free speech concerns.

“They’re not fine with a foreign adversary, as they’ve determined it is, gathering all this information about the 170 million people who use TikTok.”

Roberts went on to cite Chinese laws that require companies like ByteDance, TikTok’s Chinese parent company, to assist with intelligence gathering, asking: “So are we supposed to ignore the fact that the ultimate parent is, in fact, subject to doing intelligence work for the Chinese government?”

Because the concerns motivating the ban revolve around China’s possession of TikTok, the only hope for the app’s survival in the United States is purchase by a corporation outside of China- hence the name “Ban-or-Sell.”

“[The law is] not saying TikTok has to stop,” Roberts said. “They’re saying China has to stop controlling TikTok.”

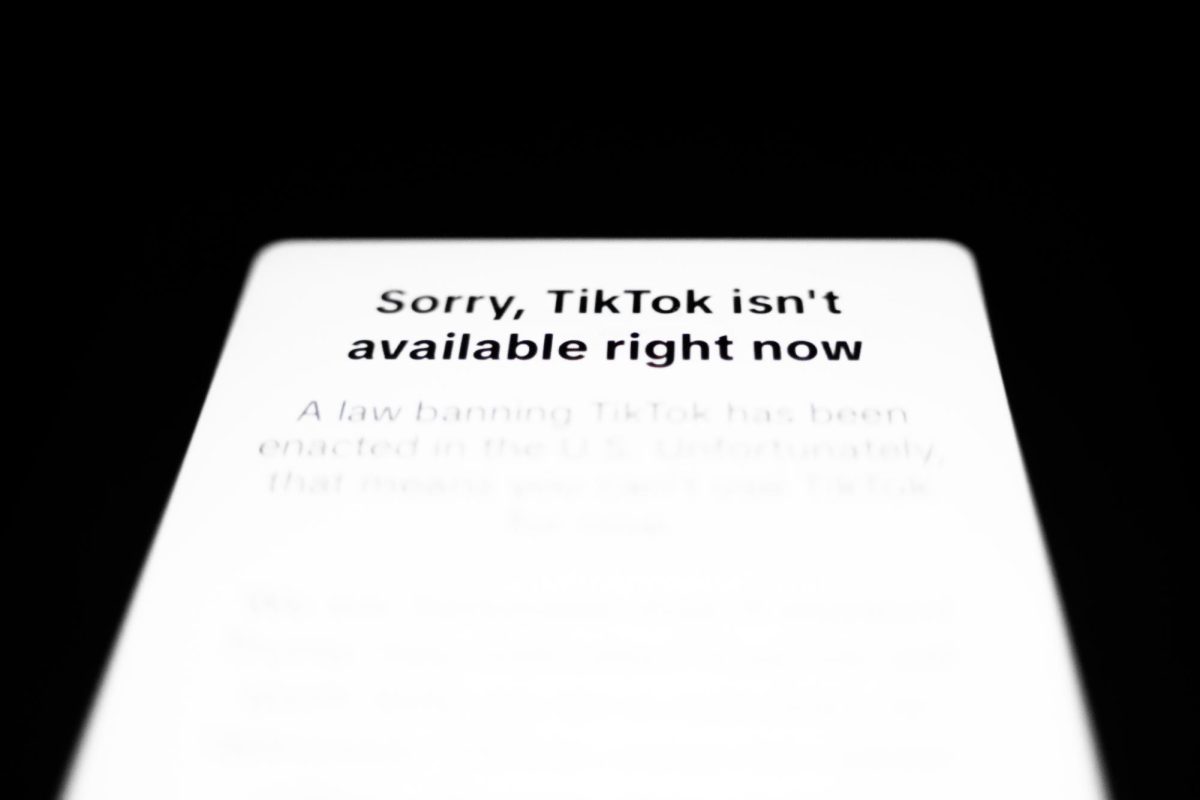

While the ban was pending, it seemed that an initiative called Project Liberty, led by billionaire businessman Frank McCourt, announced that it made an official offer to ByteDance to buy TikTok. Whether this deal will go through remains to be seen. Regardless, unless TikTok is sold to an outside corporation before January 19, 2025, TikTok will go.

If TikTok is part of the lives of 63% of American teenagers, then roughly 63% of AFS students are slated to see their chosen digital pastime disappear from their home screen within the next week- and they’re bound to have opinions on the matter.

Despite what the app’s popularity among this age group might suggest, the majority of respondents to a survey expressed some degree of apathy, or even enthusiasm, about the disappearance of this digital pastime.

In response to the question “How do you think the TikTok ban will affect your life?” Ryan Brinkerhoff ‘28 said, “It will greatly improve it.”

Tiye Abange ‘27 added, “I think it might improve my productivity because I often go on TikTok when I am procrastinating.”

Emma Hacker ‘27 said, “It may affect my life in a positive light because I will have more freedom not getting sucked into the algorithm of watching videos for hours at a time.”

Ezana Sileshi ‘25 said, “I don’t think it will affect my life at all honestly.”

Timmy Ma ‘25, Liam Hilliard ‘26, and Elise Comerota ‘28 echoed Sileshi’s sentiment, who added: “I used to use TikTok and I was addicted, so I feel like it’s better that it gets banned so that we can focus on other things.”

An anonymous student went so far as to say: “…it’s a drug for most teenagers and even adults nowadays. It’s a good thing it’s getting banned.”

While a few other respondents agreed that the ban was for the best, due to its potential to reduce doom scrolling, Aisling Scanlan ‘28 pointed out that, “a lot of people will just find new apps to be obsessed with, so it won’t get them ‘free’ from screen time.”

To that point, Jaidyn Smalls ‘27 predicts that former users will “probably just head to Instagram.”

However, Chase White ‘27 stated outright that she will “…NOT be moving to Instagram reels because it’s covered in AI and other weird videos.”

There are also students who take issue with the motivation behind and implications of the ban.

Henry Goldstein ‘27 said, “I think it is so wrong to ban TikTok. People in the government say it’s for national security reasons, but really it’s just taking away a platform where people can express themselves. I think it is hypocritical. Members of Congress that HAVE and USE TikTok voted to ban it! It makes no sense!”

Echoing the free speech argument used by TikTok’s lawyers, Hilliard added, “I’m against it for the precedent it sets. It’s not really something that’s been done in the USA to my knowledge, and it’s likely indicative of a major change in our country’s approach to media.”

Regarding the national security concerns raised by the Chinese ownership of TikTok, Neiko Savior ‘27 said, “Our government is just racist.”

A number of students pointed out the valuable by-products of TikTok that they feel themselves as well as the country will miss, one of which is its unique cultural importance.

Hacker reported, “One of my friends…said, ‘…everyone uses it and has the same jokes!’…There is probably not going to be another app that will be able to duplicate that.”

Ava Cole ‘25 said, “I think …particularly TikTok has become a defining feature of our generation’s identity.” She added frankly, “When I have a niche question, I find TikTok has the best answer to it.”

Beyond its importance as a cultural juggernaut for Gen Z, students pointed out its significance in social justice movements.

“Not only is TikTok informative and fun, but it is also great because of the activism on the app,” Abange said. “I remember after George Floyd’s death, the BLM movement created a lot of videos on TikTok to inform people about it and that created a lot of change. The same thing happened with the last elections and I feel that TikTok is powerful in that way because young people use their voices there and a lot of activists would lose their platform.”

While student opinions on the morality of the ban vary, the silver lining that its young opponents find in it is the same as the rationale of its young supporters: a step towards freedom from the stress that they admit the apps they love cause them.

Savior, who primarily disagrees with the ban, admitted: “I also think my screen time will go down so I guess that’s a plus…sometimes I wish I were a teen in the late 2000s and early 2010s because the only use of their phone was to text. Like, everyone is a screenager [screen teenager] now because of social media. It’s ruined this generation. It makes me so mad.”

Whatever their stance on the ban, the prevalence of sentiments like Savior’s amongst student respondents uncovers a lesser-known layer to this generation’s relationship with screens: though Gen Z may be just as addicted to apps like TikTok as the statistics and stereotypes say, many of us are conscious of the toxic side of that addiction and quietly long for some respite from it.